There is more to Tonbridge

than the castle, Tonbridge was granted a market charter in 1259, and there are

quite a few buildings dating from the medieval periods to be seen about the

town.

Tonbridge was originally called Tunbridge Town, and its' neighbour was Tunbridge Wells - until 1870, when the Post Office changed it to Tonbridge to avoid confusion. However, Southern Railway were running late again, and they didn't change the station name until 1929!

In 1931, Mahatma Gandhi paid a brief visit to Tonbridge, on his way to Canterbury Cathedral.

There's a program on TV this week about the last woman to be executed in the UK, Ruth Ellis. Ruth married her husband, George Ellis, in Tonbridge. George later went on to commit suicide. Ruth's was never a happy life, but from then on, it went downhill. Her boyfriend was incredibly cruel, and in 1955, she shot him dead. She was convicted of pre-meditated murder and sentenced to death. Whether she deserved that sentence, or whether she was the victim in all this, is down to personal perception. Watch one of the many films that have been made about her since, and make your own mind up.

In 2006, the UK's largest bank robbery took place at the Securitas depot in Tonbridge. £53,000,000 in unused bank notes were stolen in a very violent raid. The gang left behind £154,000,000, as they didn't have room to take it! Over 30 people were arrested and given long prison sentences, but £32,000,000 has never been recovered.

Her detailed engravings of shells were used to illustrate her father’s translation of “Lamarck’s Genera of Shells”. In 1843 Atkins self-published her “photograms” - which used a photographic printing process using light sensitive paper - in the book “British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions”. This was one of the first publications to record and present specimens in this way and so established photography as an accurate medium for scientific illustration.

Such and elegant and impressive church! It stands just off the High Street, and in the centre of the town. It was not until the 17th Century that most churches were given clocks. These were time-pieces for the town as few people had watches. The present clock dates from the 1870s

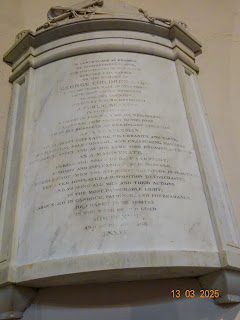

An extra south aisle was added in 1820 to serve the boys of Tonbridge School. The church is best known for its hatchments and memorials - loads of them, but too high up for me to make much sense of them.. The two most important memorials are: Lady Philadelphia Lyttleton who died in 1663 whilst attending Queen Catherine on her visit to the Wells (Tonbridge was the parish church for what we now know as Tunbridge Wells); I seemed to have missed this one, so I'll make a point of looking for it next time I go there.

In the north aisle

is the memorial carved by Louis Francois Roubiliac to Richard Children, member

of a long-established Tonbridge family who died in 1753. Particularly

well-carved is the skull with bat's wings at the base.

The Childrens were a family established in Kent since at least the 14th century, with an estate called ‘Childrens’ near Stocks Green, Hildenborough. An early George Children (1606-70) was educated at Tonbridge School and became curate at the parish church.

Richard Children lived at Ramhurst Manor, Leigh until his death in1753 (and was allegedly still haunting it a hundred years later). His memorial carries verses by James Cawthorne, the headmaster of Tonbridge School at the time.

Richard’s son John (1706-71) was the first to live in Tonbridge town, moving to Ferox Hall in about 1750 and adding the present brick frontage to the existing house a few years later.

John Children was succeeded at Ferox Hall by his son George (c1742-1818), the first member of the family to play a major part in the town’s affairs. A barrister who never practised, he was a JP for half a century, under-sheriff for Kent and Sussex, a proprietor of the Medway Navigation Company, and one of the founders of the Tonbridge Bank.

He was also a close and devoted father to his only son, John George, whose mother died six days after giving birth to him. George was a kindly and much-loved Tonbridge figure, as his memorial in the parish church attests

John George Children (1777-1852) was a scientist at a time when science was still largely a pursuit for gentleman amateurs. He was well-known in London scientific circles, was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society at the age of 30 and later became its Secretary. His particular interests were in electricity and the chemistry of minerals.

Following his education at Tonbridge School, Eton and Cambridge, he married, but like his father soon became a widower when his wife died a year after the birth of their only child, Anna. After a period of foreign travel, including a visit to the United States and Canada which was cut short by ill-health, and a rock-collecting trip to Cornwall and Wales, John George returned to Ferox Hall and began to devote himself to his scientific pursuits, working in the purpose-built laboratory in the grounds of Ferox Hall.

In 1808 John George was involved in an accident when a sudden conflagration during an electrical experiment threw caustic alkali into his eyes. Luckily the damage was not permanent, but he advised anyone involved in similar work always to wear goggles. The Childrens went on to construct the famous giant battery of 1813.

In 1811, John George was involved in setting up the Tunbridge Gunpowder Company, together with his father, on whose land at Leigh the Powder Mills were built, and other backers. Humphrey Davy, a close friend, was also briefly involved in this enterprise.

By 1813 the Tonbridge Bank was on the point of collapse, bringing financial ruin to the Childrens. Ferox Hall eventually had to be sold, and they moved to London, where John George had to start earning a living. A post was found for him at the British Museum, and he served there in various capacities for more than 20 years.

John George died in January 1852 at his daughter Anna's home in Halstead and is buried at St George's, Bloomsbury. His name is commemorated in an Australian snake‚ Children’s Python‚ and a mineral, childrenite.

John George Children’s only child, Anna (1799-1871) was brought up by her father and grandfather in the lively family home at Ferox Hall. From her father, to whom she was particularly close, she gained practical skills and a love of science unusual in a woman at that time. She was a botanist and also an excellent illustrator who contributed more than 200 drawings to a book on shells which her father had translated from the French.

In 1825 she married John Pelly Atkins, who would later become Sheriff of Kent, and it is as Anna Atkins that she is best known – better known in fact than her father or grandfather. There were no children and Anna devoted much of her later life to photography, a field in which she is a notable pioneer.

The Childrens were friendly with two other important figures in the history of photography, W. H. Fox Talbot and the astronomer John Herschel. Herschel devised a photographic technique known as the cyanotype process, in which paper was impregnated with a material which turned blue when exposed to light, producing what were later known as blueprints. Anna Atkins used this technique to create shadow images of botanical specimens, a pioneering application of photography to science. Over ten years she was personally responsible for the production of the more than 400 cyanotype plates needed for each copy of her book ‘Photographs of British Algae’, based on her own seaweed collection. This book was the first ever produced wholly by photographic means.

Anna died in 1871 at her home, Halstead Place, between Knockholt and Chelsfield.

He had a residence in Tonbridge as well as two in London. The inscription by his tomb names Sir Anthony as "one of the Honorable band of Pensioners (both to our late, renouned Lady Q Elizabeth, & also to our now soverain Lord K James)". The Gentleman Pensioners were an elite group of fifty knights, established by Henry VIII as royal bodyguards. Account rolls from the time tell us Sir Anthony served in this position from 1602 until 1615, and this may account for his prominent burial in the church; above him is his funeral helmet, the mark of a Knight.

The window was installed in 1954 after the plain glass window was destroyed by a flying bomb in 1944. Leonard Walker collected these pieces of coloured glass from all over the country, fitting them together into his overall design. In this way the window also represents how people of all shapes and sizes, from all places can come together as Church in worship of Jesus Christ.

Leonard Walker was 80 when he designed and made the window, which took three years. He was paid £8 a week, which was a working man's wage in the 1950s.

Tonbridge Castle is an

imposing Norman motte and bailey fortress protected by a massive gatehouse. The

castle may be the best example in England of the motte and bailey style so

favoured by the Normans.

A magnificent medieval

gatehouse fronts the remains of Tonbridge Castle, begun by Richard Fitzgilbert,

a relative of William the Conqueror. Fitzgilbert's simple fortification was

replaced by a massive stone structure which was added to and remodelled over

the centuries.

After the Norman victory at

the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror gave lands to his most

powerful supporters at key points around his new kingdom. One of these key

points was the crossing of the River Medway at Tonbridge.

William entrusted the

Tonbridge crossing to a kinsman named Richard Fitzgilbert. Fitzgilbert held

estates throughout the south east of England, including one at Clare,

Suffolk, and his family eventually became known as the de Clares.

Fitzgilbert erected a

traditional motte and bailey castle, with a timber fortress atop an earthwork

mound, surrounded by an outer enclosing bank and ditch topped by a palisade.

In 1088 the de Clare family

joined a rebellion against William II. The king's army besieged Tonbridge

Castle and the rebel garrison was forced to surrender. The town was burned by

the royal army, yet de Clare was allowed to retain ownership of the castle.

Given the enmity between the

de Clares and the king, it may be no coincidence that the arrow that

accidentally killed the king in 1100 was shot by Walter Tyrell, a son-in-law of

Gilbert de Clare.

In the middle of the 12th

century, a dispute over the castle broke out between the de Clares and the

Archbishop of Canterbury, who claimed that the de Clares held Tonbridge from

them, not from the crown. In 1163 the Archbishop sent a messenger with a document

outlining his claims, and Roger de Clare forced the messenger to eat the entire

document, including the parchment and seals.

The de Clare's supported the

Baron's Revolt against King John, leading to the Magna Carta in 1215. King John

retaliated by besieging Tonbridge Castle and the defenders were forced to

surrender. However, John died shortly thereafter and Tonbridge was restored to

the de Clares by Henry III.

When Gilbert died in 1230 the

wardship of his young son Richard was given to Hugh de Burgh, who was given the

castle in trust. The Archbishop of Canterbury also claimed the wardship and

excommunicated de Burgh after Sir Hugh secretly married Richard de Clare to his

daughter.

Affairs took an even more

confusing turn when Henry III supported de Burgh, yet annulled the marriage and

took Richard as his own ward. The Archbishop appealed to the Pope, who, not

surprisingly, supported his claim, but the Archbishop died on his way back from

Rome.

Around 1253 Henry III granted

Earl Richard the right to build town walls and crenellate Tonbridge, and the

castle as we see it today began to take shape. Richard's son, another Gilbert

de Clare, supported Simon de Montfort's rebellion against the king, and in 1264

Henry besieged and captured the castle.

De Clare was reconciled to

the king, and in 1270 he welcomed Edward I and Eleanor of Aquitaine to England

and entertained the new monarchs at Tonbridge Castle.

The castle passed through

marriage to the Stafford family but eventually became Crown property and was

granted to a succession of royal favourites. At the time of the Civil War, it

was owned by Thomas Weller, a Parliamentary supporter.

The castle was slighted during the Civil War, and during the 18th century stone from the castle was used to build bridges and locks along the River Medway.

Tonbridge Castle is extremely

impressive; though little remains of the keep, the Norman motte and the

castle's perimeter walls are striking, but by far the most impressive castle

feature is the gatehouse, which is really a miniature fortress in its own right.

No comments:

Post a Comment